A Kayan Lahwi Woman

Sitting on a teak staircase in a weaving factory on Inle Lake, a woman wearing a colourful headdress and brass neck rings poses.

Inle Lake in the Shan Hills of Myanmar may not be particularly large, but it is rich with culture.

Its shores are laced with canals and waterways that give access to cities and villages housing about 70,000 people. Inle Lake is as ethnically diverse as the Shan State as a whole; pockets of Intha (“People of the Lake”), Shan, Taungyo, Pa’O (Taungthu), Danu, Kayah (Karen), Danaw, and Bamar live on the waters and around the shores. Regardless of ethnicity, most of the people here are devout Buddhists who live largely traditional lives in simple wood and bamboo houses – often on stilts over the water.

The people on the lake are largely self-sufficient, living on their fishing and farming. Extra household income comes from the making and selling of handcrafts – the area is well known for its woven textiles and hand-rolled cheroots in particular – and from the relatively newly burgeoning tourist trade.

I’ve posted photo-stories from this area before (see: Inle Lake). Join me for another boat trip on these beautiful Burmese waters.

Boatman on Inle Lake

As I have said before, the only practical way of getting around on Inle Lake is by boat.

Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda

Regardless of ethnicity, most communities around the lake are Buddhist. Some of the temples are just stunning – and represent real feats of engineering and architecture, built as they are, over water.

Boatload of Produce

Much of the boat-transport on the lake is by low-riding wooden paddle boats.

Wooden Thread Frame

The stilted teak buildings in Inn Paw Khon Village are home to a thriving cottage industry in silk and lotus weaving.

Woman Spooling the Thread

The weaving “industry” is labour intensive: this woman had to walk up and down the length of the frame with her silk threads many, many times…

Ikat

… before the threads are tied off for dyeing. Ikat (known as mut mee in Laos and Northern Thailand) is a complex dyeing technique used to pattern textiles: warp or weft threads are tied off in a pattern before the threads are dyed and then woven.

Worker Next Door

The buildings are so close that you can see across the water and in through the window to the dark workspace next door.

A Weaver

Inside the factory is dark, with light angling through the open windows.

The Loom

The wooden looms for weaving the lengths of silk fabric are large and complex.

Elderly Woman Spinning

People use their skills as long as they are able…

Weaver’s Hands

… performing delicate and intricate work …

Elderly Weaver

… for long hours and little pay.

Weaver in the Light

The work is repetitive and requires concentration.

Lotus Fibres

Inle Lake is the only place in Myanmar where the unique fibres from the lotus plant are produced. These are then woven into special kya thingahn (lotus robes) for Buddha images.

Dyeing Cloth

Lengths of cloth are hand dyed in buckets.

Rolling Cheroots

In Nam Pan Village, on the opposite side of the lake, young women roll cheroots. The cigars come in a variety of sizes and flavours: the crushed tobacco and bits of dried wood can be flavoured with dried banana, pineapple, tamarind, honey, rice wine, or spices, before being rolled in thanal-phet tree leaves.

Young Women

Their fingers are quick – but they still have time to check out the visitors.

Young Woman in Thanaka

Ubiquitous in Myanmar, thanaka powder – made from ground bark – is used for cosmetic beauty and to prevent sunburn. It also has anti-fungal properties.

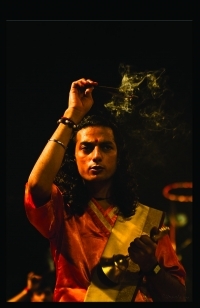

A Kayan Lahwi Woman

Nearby, a bamboo and teak building houses a Kayan (Red Karen) gift shop.

Woman on the Stairs

Often referred to as Padaung – Burmese for “Long Neck” – women in the Kayan Lahwi group or “tribe” wear brass rings around their necks, arms, and legs from an early age. The weight of the brass rings on the neck pushes the collar bone down and compresses the sternum and rib cage, giving the neck its lengthened appearance.

No one seems to know why the Kayan Lahwi started wearing the rings. Some stories say it was to protect them from being attacked by tigers, others say it made them look like dragons, and others say it protected the women against the slave trade. Today, most the women will simply cite tradition and beauty.

Historically from the Karenni (Kayah) State, many Kayan Lahwi moved into the Shan State and neighbouring Thailand in the 1980s and early 1990s because of conflict with the military regime. In Thailand, because of their unusual appearance, they became political pawns, and were set up in camps as tourist attractions which have been described as “Human Zoos”.

Kayan Lahwi Women

Women these days tend to wear fewer neck coils – and some don’t wear them at all.

Back Weaving

Like other Karen groups, Kayan Lahwi women practice back weaving, using a back strap loom. Light and portable, back looms allow you to weave anywhere, but the pieces can be no wider than your hips.

Back Weaving

The Kayan Lahwi women work mostly in cotton and synthetic fibres, weaving brilliant pattern, making the traditional scarves and tunics.

I’ve met a number of Kayan Lahwi women over the years, and they have always struck me as intelligent, self-possessed people who are neither pawns nor fools.

Tourism is a double-edge sword: traditional communities and their handicrafts can benefit from the direct financial input of the tourist dollar, but they are also at risk of exploitation by unscrupulous operators, and risk the distortion of values that a sudden influx of money can bring.

I hope that these traditionally self-reliant communities can find away to improve their own lives without losing those things they consider important.

I hope that these traditionally self-reliant communities can find away to improve their own lives without losing those things they consider important.

Till next time ~

Pictures: 21-22September2012

.jpg)

.jpg)