It’s guinness time; time to meet me at the pub!

Can you get more Irish than Dún Chaoin (Dunquin) and An Daingean (Dingle), on the Corca Dhuibhne (“Seed or tribe of Duibhne”; the Dingle Peninsula) on the southwestern-most reaches of Ireland’s County Kerry?

I very much doubt it!

After staggering into Dingle from Annascaul, wet and windblown, we were pleased to have two nights in one place and an official “rest day” on our walk around the Dingle Peninsula.

The guide notes were right!

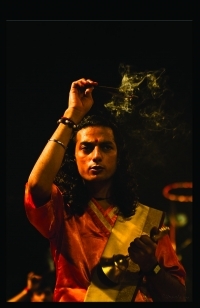

Dingle is delightful. We ate fish and chips and mushy peas while the football played on the TVs one evening. The next night, as we were listening to an old and expert fiddle player, we and our tables were pushed back to make space for the dancers. Not the Irish Dancers we know from television: those unsmiling girls in short kilts whose legs stomp and twist while their arms never move. No, these were four pairs of everyday-looking people who turned into whirling dervishes once the fiddler took up his bow: swirling and spinning around in patterns so fast and complex my head spun just watching them.

Pretty, even in a drizzle and under gray skies; Dingle, Co. Kerry.

National Geographic once called Dingle ‘the most beautiful place on earth’. Even in the morning drizzle, with gray skies overhead, it is a pretty town.

Of course, I was loath to waste our day in Dingle “resting”, so we caught a lift to Dunquin to catch a boat to the Blasket Islands – or so we had hoped. With the rough weather, the boats weren’t making the crossing, and we settled for a few interesting hours in the Great Blasket Centre instead.

An exhibition of photographs of the residents and houses, etc, from Great Blasket Island.

The unnamed statue that I like to call “Against the Wind” evokes the feeling of hardship on the island.

It looks calm enough today – Great Blasket Island, off the southwest coast of Ireland.

This whole area is Gaeltacht – the Irish language word meaning an Irish-speaking region – and Great Blasket Island was the language cradle that allowed this to happen. By the end of British rule in Ireland (1920-22), Irish Gaelic was spoken by less than 15% of the population. Great Blasket Island (An Blascaod Mór), however, sitting off the coast, with no modern conveniences, no priests, pubs, or doctors, was fairly isolated, allowing the old language to survive and thrive. The small community (160 people at most) that lived there until the final evacuation in 1953, had rich oral traditions, which they were encouraged to write down after visits by Irish scholars and poets in the early twentieth century. This led to a remarkable number of writers who published works in Irish; many of which have been translated into other languages. Spoiled for choice in the Visitor’s gift shop, we settled on “Twenty Years a-Growing” by Muiris Ó Súilleabháin (Maurice O’Sullivan), first published in 1933, and read by me with a smile on my face.

Once finished at the centre, we booked a cab to meet us later at a local pottery workshop, and set off walking across the roads and hills.

Wind-swept and isolated – the houses of Dunquin, Co. Kerry.

Looking back down the quiet roads…

Tiny flowers grow in the stone walls along the roadway.

House on a hill.

Curious, we followed the bus-loads of tourists up the stony hills at Clogher Head.

We were greeted by large granite rocks –

– and treated to a fabulous view!

The little beach of Clogher Strand, Ferriter’s Cove and, in the distance, the peaks of The Three Sisters.

Flowers on the Edge

Like something out of the “Irish Spring” commercials of my youth, a woman – dwarfed by the landscape – runs down the hill…

Cape, Cove and Cave:

The beach at Clogher Strand, Ferriter’s Cove and, the mountains the distance.

Daisies growing wild. Ballyferriter, Co. Kerry

Standing stone with a viewing hole –

– lined up with another stone with another viewing hole.

Some properties have a killer view!

Strange creatures greet us as we finally reach the Louis Mulcahy Pottery complex in Clogher –

– while other works, like the beautiful pieces for sale inside the shop, are the epitome of stylish grace.

Back in Dingle, the afternoon sun shines long enough for us to get from one shop to another.

Ceramic babies in the shops are ready for the extremes of local weather.

Young women take advantage of the sun to get their hair decorated…

… and women walk home with their shopping.

Back in Dingle, during intermittent rain showers, we browsed in shops displaying local pottery, woven and knitted goods, jewellery, musical recordings and instruments. When the sun came out, we enjoyed locally made ice cream. Everywhere, we heard people speaking Irish Gaelic between themselves, before switching to English to speak to us.

Modern expressions of age-old crafts, language and music are alive and well here, and it was a joy to partake – even if only for a day.

Sláinte!

Pictures: 22June2012

.png)

Ursula, thank you for this report. photos of a really beautiful landscape and the ceramic babies are lovely. I wish you a pretty weekend, Dietmut

Thanks for your visit, Dietmut!

We really enjoyed this part of Ireland – in spite of the rain. I hope it is not too cold where you are. 🙂

[…] by bus, and then from Camp by foot. We had spent days trudging through rains, down country lanes, into museums and shops and churches, over hills and through bogs, over mountains and across beaches. We were sore and […]