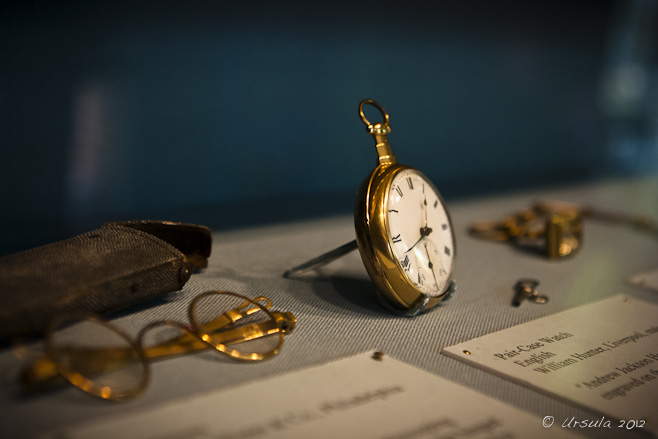

Standing the test of time ~ Some personal effects of General Andrew Jackson; seventh president of the United States.

How will you – or I – be seen in the future; say, one- or two-hundred years from now? What legacy will we leave? How will we stand up against the changes of mores and values that take place over time?

I had cause to think about this last week while visiting The Hermitage, the home and plantation of Andrew Jackson, the controversial seventh president of the United States.

Magnificent eastern red cedar (juniperus virginiana) in the grounds of The Hermitage.

“He blazed new trails and opened new possibilities. He was loved and loathed… revered and reviled… but seldom ignored.”

– The Hermitage

The legacy of General Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) is mixed indeed.

He was part of the Revolutionary War for American Independence by the age 13, and later, as Major General of the Tennessee Militia in 1812, he was responsible for leading a force of militia and irregulars to victory against the British at the Battle of New Orleans. But, he also participated in a number of questionable duals: leading to at least one death.

He adopted an orphaned Creek Indian boy, Lyncoya, (c1811-1828) and raised him with his nephew, whom he also adopted. But, he signed off on the Indian Removal Bill (1830) which forced Native American nations from southeastern United States (Cherokee, Muscogee [Creek], Seminole, Chickasaw, Choctaw and others) off their lands. In what is now called the Trail of Tears, Native Americans were forced-marched, suffering great hardships and loss of life, out of their homes and to the “Indian Territory” in what is now Oklahoma.

He reputedly adored his wife, Rachel, and in true frontier style, married her before she was officially divorced from her first husband. He defended her honour vigorously, and blamed his political opponent, John Quincy Adams, for her death after a particularly dirty political campaign. Even so, Jackson ridiculed the fight of women for the vote.

After Jackson’s first electoral campaign of 1824-1825 – where he received the most popular and electoral votes, but was defeated by John Quincy Adams in the House of Representatives – the Democratic Party was formed as a vehicle to lobby for him, leading him to win in his second campaign. In spite of several controversial decisions, he won a second term, serving the maximum-allowable eight years: from 1829-1837. He was a champion of “the humble members of society – the farmers, mechanics and laborers…” And yet he sent troops to quell labor disturbances on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canals.

His belief in democracy was like that of the Romans: only open to free white males. Voting rights for women, Blacks and Native Americans were never even considered. His own estate, The Hermitage, which he bought and operated from 1800, only prospered on the backs of the 150 slaves which he owned.

As I walked around the property, which is now owned and operated by the Ladies’ Hermitage Association, these contradictions were very much at the forefront of my thoughts.

The mansion at The Hermitage was designed with a “Greek Revival” style facade to symbolise American’s love of liberty and democracy.

Orchards and gardens are a large part of The Hermitage’s extensive grounds.

Bill, one of the costumed “Historical Interpreters” who act as guides within the manor. No photography is allowed inside the house.

Daisies in the gardens.

Surrounded by gardens: the tomb of Andrew Jackson.

Delicate life: small dragonfly against the tomb of General Andrew Jackson.

One of the many memorials and headstones in the Jackson family plot: Thomas Donaldson Lawrence, Jackson’s great grandson.

Butterflies in the gardens of the family plot.

Cosmos around the headstones.

The slaves’ quarters are well away from the main house.

Some of the modest cabins which served as slaves’ quarters have been restored.

Alfred was born (as a slave) at The Hermitage and lived and worked there all his life. He was still on the property when it became a public museum, and, at his request, is buried in the family plot.

The reason for the slaves: cotton plants are labour-intensive, and plantation owners did not believe they could grow a competitive crop without free workers.

A delicate cotton flower hides among the green stems and leaves.

The corn crops have died all over the United States this year as a result of drought conditions.

Turkeys in the grass – on the run.

Bell at the back of The Hermitage mansion.

The ultimate in irony? Bobble Heads of President Andrew Jackson, Uncle Sam and other presidents in The Hermitage Gift Shop.

Winds of change? A bronze horse sits in the gift shop window.

While Jackson reserved his idea of “democracy” for a select few, what he did was to set in motion a process of political party politics. The Democratic party, his legacy, was an electoral machine whose organization and discipline would serve as a model for all others. The groups he excluded from power have used the process he set in place to redress the balance.

As I said earlier: a mixed legacy.

As I said earlier: a mixed legacy.

But, one worth remembering.

What will ours be?

Photos taken: 24August2012

.png)

Lovely history lesson Ursula – love the pics, especially the daisy one.

Anna :o]

I love that you don’t just visit places Ursula, you absorb them, what a wonderful trait, even better that you share it.

as to the legacy, ask me after Saturday LOL

Many thanks to my two Liverpool Ladies. 🙂

Eight years was not the “maximum allowable” time Andrew Jackson could have been president. There was no limit then.

Franklin D. Roosevelt served for 12 years and was actually elected to four terms, which would have totaled 16.

This was changed by adoption of the 22nd amendment to the US Constitution on February 27, 1951. Since that time, no one can be elected president more than twice. Anyone who succeeds to become president can only be elected once, if they serve for more than two years of someone’s term.

Therefore, as a practical matter, the absolute limit on how long someone can be president now is 10 years.

Thus Lyndon Johnson, who became president after the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963, was still able to run for reelection in 1968. If he had been reelected, his total time in office would have been more than 8 years but less than 10.

On the other hand, if Gerald Ford had been elected in 1976, he would have been limited to one full term in office, plus the 2 1/2 years he served once Nixon resigned from office in 1974.

Many thanks for the correction, David. 😀