What we think we need is so dependendent on what we already have.

Earlier this week, my husband and I drove the six-plus hours south from Sydney to Eden, a coastal town in New South Wales, Australia. We are having some work done on a small house we bought there in preparation for our relocation at the end of the year. I had gone to some effort to ensure we had the electricity turned on in time for our arrival, so you can imagine my frustration when we got there in the dark and turned on the power mains, only to have the hot water system go: “Snap! Crackle! Pop!” like the popular breakfast cereal, before starting to smoke.

Although I confess to feeling momentarily sorry for myself about not being able to wash my hair and about having to sponge-bathe with hot water from the kettle, I couldn’t help but think back to the few hours I spent on Tonlé Sap Lake in Cambodia earlier this year. As part of a photographic expedition led by Karl Grobl, Gavin Gough, Marco Ryan and Matt Brandon, I spent an overcast morning on a boat on the famous “rising” lake.

Monks' laundry hangs at the "boat dock" on the edge of Tonle Sap at Kampong Khleang.

Boats sit surrounded by edible Chinese water morning glory at the "dock" at Kampong Khleang.

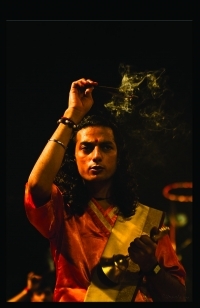

Work starts young ~ our boat 'man' pushes us away from the dock.

Designated as a UNESCO biosphere, Tonlé Sap is the largest freshwater lake in South East Asia. The lake is responsible for 75% of Cambodia’s national inland fish production. Around 3 million people live on or around the lake, making a living fishing the many commercial species of fish, turtles and snakes, or farming the rich soils.

Houses rise high over the low waters of Tonle Sap before the monsoons fill the lake ~ boat, floats and fish-farms sit below.

Whether it is to go grocery shopping or to visit neighbours, everything is done by boat.

Houses rise up on stilts behind tall grass at the moveable shoreline, Tonle Sap Lake.

Tending the fish-traps is no easy task!

Checking the lines and nets.

The local pot shop?

Fresh paint and cheerful plants on a floating house: some house-holders take pride in their surrounds.

A young girl with the family dog, on the "porch" of their floating house.

The living is not easy, however. Every year when the Mekong floods during the June-July monsoons, the Tonlé Sap river flows backwards and the lake level changes from about 1meter in height to as high as 10 meters. Local residents accommodate these drastic changes by either building on high stilts, or floating their houses on old drums. We cruised past, like voyeurs, sitting in relative comfort watching people go about their daily lives: fishermen standing waist-deep in water with nets or fishtraps and women washing cloths by hand or taking the boat to market. We dropped in on the local “fish market”: an exchange of goods and money that takes place in the middle of the lake.

Daily wholesale fish markets ~ Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

Fish exchange, Tonle Sap Lake

The Fish Buyer ~ Fish Markets, Tonle Sap

Tallying the Purchases: Fish Market ~ Tonle Sap

Fish scales ~ Tonle Sap

There are 200 types of fish in Tonle Sap; 70 of which are of commercial value. There are 23 snake species, which are being harvested unsustainably, and 13 turtle varieties, as well as a native crocodile.

An insurance adjuster once said to me that the losses from huricane Katrina were much worse than from the tsunami in South East Asia: because the people had more to start with, they had more to replace. I suppose that is one way of looking at things, but it is interesting to me that those of us who have more, really can’t conceive of managing with less – like my “need” for hot water on tap.

It also makes me wonder about how we “value” things. On Tonlé Sap, where people have so much less than most of us reading this post, and where they work long hours eking a living from their surroundings and doing their daily chores, they still have time to smile and wave at passing tourists.

Old boat ~ Tonle Sap

Visiting, or being a voyeur is one thing, but if we had to change places, I don’t imagine I’d do very well. I keep trying to make my life simpler, but I admit, there is probably more in my suitcase than in some of these homes.

Visiting, or being a voyeur is one thing, but if we had to change places, I don’t imagine I’d do very well. I keep trying to make my life simpler, but I admit, there is probably more in my suitcase than in some of these homes.

And yet, they keep smiling.

.jpg)

Enjoyed it very much especially knowing the effort that went into this one. Excellent as usual

Fabulous as always, I was thinking just prior to your comment how these people always smile, waist deep in water working yet the smiles are so genuine and friendly… simplifying sounds great especially when we see greed in our society taking forefront to almost everything else. whats the old saying, there but by the grace of God go I….thanks as always

Lovely series of photos and explanation. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks so much, Patrick!