Two Theravada Monks at Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat.

There can be no symbol more iconic of Cambodia’s attempts to guard its glorious Khmer past or of it’s hope for a self-determined future. The world’s largest religious monument, built between 1113 and 1150 during the reign of Suryavarman II, Angkor Wat was designed as a microcosm of the Hindu universe. The outer moat represents mythical oceans, while the concentric galleries stand for the mountain ranges that surround the inner sanctum, Mount Meru, home to the Hindu pantheon.

Vishnu the Protector ~ This statue, now in the West Entrance gopura, is believed to have been originally located in the central sanctuary.

Although built as a palace for the Hindu gods, Angkor Wat has always been religiously inclusive: first with respect to the original Khmer deities, and later to Mahayana and Theravada (Hinayana) Buddhism, respectively. Today, Hindu and Buddhist devotees intermingle freely as they pay their respects and/or pray at alters to their own or each other’s gods.

Reclining Buddha ~ Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat is so integral to Cambodia’s sense of self that it is a part of the national flag: the only building in the world to be so honoured. The black and white outline of the temple’s three towers against the red and blue of the flag match the view that greets you as you approach from the causeway on the the west side, as most visitors do.

The first time I went to Angkor Wat (in 2007) I, too, entered from the west – as witnessed by the dawn photograph I have in the opening masthead series (above). This July, as part of the photo-tour/workshop with photographers Karl Grobl, Marco Ryan, Gavin Gough and Matt Brandon, I visited the temple twice: both times in the late afternoon, both times entering from the east; essentially coming in the ‘back door’. It was quiet – no tourists – no hawkers – only one lone fisherman, illegally trying to catch dinner in the moat until he saw our cameras – and we could have been the first ‘outsiders’ there.

Lathe-Turned Stone Window Balusters, Angkor Wat

The bas reliefs of Angkor Wat are justifiably famous: covering extensive areas, the exterior wall panels of the third enclosure tell ancient Sanskrit creation stories and epics, particularly the Mahabharata, the philosophical and devotional story of a dynastic struggle for power, and the beloved Ramayana, the epic poem series depicting the major events in the life of Rama, an Avatar of Vishnu. But it is not only the walls. Almost every surface is carved: from the lathe-turned window balusters to the heavenly apsara dancers gracing walls and pillars everywhere.

Apsara Dancers inside Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat is so much more than relics in stone. The organisation that looks after this, and other Angkor temples in the Siem Reap area, is APSARA (Authority for Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap), which was created by royal decree in 1995 in response to the need for local planning for World Heritage Listing. The acronym makes reference to the apsara, the celestial nymphs of Hindu and Buddhist legend, who also lend their name to traditional Khmer classical dance-drama performance. The agency is the link between local management of Khmer cultural heritage and UNESCO; and the guards, guides and various workers around the grounds all wear their APSARA name-plates proudly.

APSARA Employee, Angkor Wat

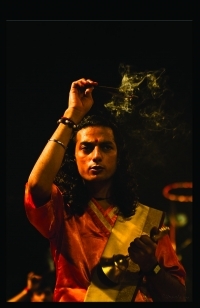

Above all, Angkor Wat is a temple; a site of pilgrimage and active worship for Hindus and Buddhists alike, Cambodian and otherwise. The saffron robes of Theravada monks are ubiquitous – it’s as if the monks are scattered, posed, just waiting to be photographed against the richly coloured weathered stone walls.

Monk in the Balusters

Monks in the Corridors, Angkor Wat

Cultural Exchange: A French woman discusses modern Buddhist practice with a young monk

Monks in the Afternoon, Angkor Wat

The stories told on the walls of Angkor Wat still live in the hearts and minds of the people, as well as in the modern practice of Khmer classical dance. The Cambodian version of the Ramayana, the 24,000 verse epic poem about ‘Rama’s Journey’ through life, integrates Buddhist themes into the traditional Hindu stories. One of the pivotal chapters tells how Rama’s wife Sita is abducted by the demon king of Lanka, Ravana. Another depicts her subsequent rescue by Hanuman, the monkey god. Our photographic mentors, Gavin Gough and Matt Brandon managed to persuade three apsara dancers to meet us in the corridors of the wat for a late afternoon photo-shoot.

Just for us! Khmer apsara dancers and the Ramayana: Ravana, Hanuman, and Sita in the west corridors of Angkor Wat.

Hanuman Strikes a Pose

Hanuman’s Hand

Sita’s Feet

Corridors of Power: Ravana Unmasked

Beauty and Strength ~ Ravana Unmasked

So, Angkor Wat may be a monument to a glorious Khmer culture of times past, but it also houses ongoing religious practices and modern renditions of ancient stories. It is a living monument.

Given the tragedies of recent Cambodian history, I hope that the cultural heritage embodied in this iconic temple can help the Cambodian people bridge the gaps between their cultural past and their potential future.

‘Till next time.

.png)

WOW, amazing the detail and intricacy of the stone work, and what beautiful shots of the dancers, Ursula you are certainly living the dream… thank you for sharing it.

Cheers, Signe! 😀

I have seen a lot of these images on Flickr too. A very interesting

story Ursula. Fine sunday, mgreetings Dietmut